From Spaced Repetition Systems to Open Recommender Systems

Wouldn't we be happier if our flashcards competed for our attention by being more interesting as opposed to more difficult?

This is the same as the version that was originally posted on my dev.to account with an added article voiceover so you can listen to it instead.

In this piece, I want to connect YouTube Shorts and TikTok to spaced repetition and incremental reading which I've worked on for the past 4 years.

If you think about it, all of these systems fall into the general bucket of "recommender systems" - systems which attempt to predict and provide content that is most relevant to the user based on their past interactions.

I made the connection while working at RemNote and thinking about ways to make the spaced repetition review experience more enjoyable - why do people kick back and relax at the end of a long day by watching four hours of YouTube shorts, but find 10-minute Anki review sessions to be a miserable chore? Is the only way to make flashcard queues more engaging to make the content more sensationalist and "trashy" similar to YouTube shorts and TikTok, or can you become addicted to educational content that helps you improve your life and make progress towards your goals?

I want to explore the potential for a system that borrows the best elements from each to create something that feels as effortless and engaging as a queue of YouTube shorts but actually helps you make progress towards meaningful goals.

A Recommendation System for Your Memory

Spaced repetition systems (SRSs) are digital flashcard managers like Anki, SuperMemo and RemNote. You can think of them as recommender systems for your memory which direct your attention towards information you are about to forget.

While they are extremely effective at combatting forgetting, many users struggle to maintain consistent review habits because the system prioritises showing you information that you are about to forget over information that you would find interesting.

How Spaced Repetition Works

Spaced repetition systems use algorithms which calculate the optimal review times and fewest repetitions required to keep flashcards in your memory. The intervals between reviews expand with each repetition allowing you to maintain your knowledge with exponentially lower effort over time.

By controlling the rate of forgetting, you eliminate the churn effect in learning. Without spaced repetition, your knowledge grows asymptotically towards a saturation level as the rate of forgetting old knowledge balances the rate of learning new knowledge.

Spaced repetition linearises the acquisition of knowledge. By calculating optimal review dates and exponentially increasing review intervals, a single flashcard may be repeated as little as 6-20 times across your entire lifetime, meaning that you may be able to remember as many as 250-300 thousand flashcards by the time you retire.

Why Hasn't Spaced Repetition Taken Over the World

Spaced repetition has proved itself to be an effective learning technique across a wide range of disciplines, from language learning to medical school, mathematics and coding.

I used Anki to learn Chinese to the point where I can comfortably read science fiction like The Three Body Problem without a dictionary. I used SuperMemo to learn coding from scratch with no technical background which then became my full-time job. And I used RemNote to learn math, later writing an intro to logic and proof course using an interactive theorem prover and RemNote as someone who hadn't studied math since I was 16.

Spaced repetition can change your life and it has the potential to change the world, but it's rare to see it used outside of cramming for exams (language learning being the major exception). Students endure the spaced repetition algorithm until they graduate and feel a great sense of relief when they can finally delete their flashcard decks for good. Burnout is also common with many users feeling crushed by their daily repetitions.

Misaligned Objective Function

The objective function of the spaced repetition algorithm is to maximise the user's memory retention with the fewest number of repetitions. I've argued before that this is often out of line with users' real-world goals and makes it hard to enjoy the review experience.

Because the goal is to maximise memory retention, the bulk of your reviews will be focused on the flashcards that are most difficult for you. From the perspective of the spaced repetition algorithm, it would be considered a waste of time to review flashcards that you easily remember because if you can easily remember them, the system can confidently boost the review interval far into the future, satisfying its goal of minimising your repetition load. Instead, it's considered better to show you the cards you find most difficult more often so you can burn them into your memory.

As a result, reviewing your flashcard queue becomes a punishing experience where you are predominantly reviewing information you don't understand very well. Avoiding this requires quite a lot of attention and care, obsessing over flashcard formulation, eliminating leeches and aiming for a consistent 90% retention rate.

Here's another way to think about it: in a pure spaced repetition system flashcards compete other flashcards for your attention by being more difficult to remember. Wouldn't we be happier if our flashcards competed for our attention by being more interesting as opposed to more difficult? I realised that this is effectively how recommender systems like YouTube and TikTok work - they are markets of video clips competing to be as interesting and engaging as possible for users. This thought is what got me interested in studying them more closely.

Incremental Reading

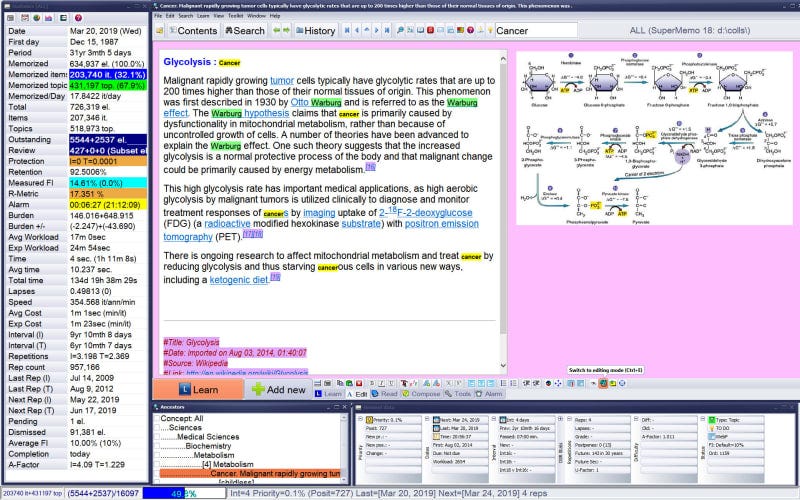

Incremental reading systems like SuperMemo are a superset of spaced repetition systems. Incremental reading involves interleaving your flashcards with snippets from articles, books and videos in a big prioritised queue.

The general idea is to form a "funnel of knowledge" in which a vast worldwide web is converted into a "selection of own material", that moves to important highlights (extracts), that get converted to active knowledge (cloze deletion), which is then made stable in memory, and, in the last step, acted upon in a creative manner in problem solving. - Incremental Reading

It's interesting to analyse them through the lens of recommender systems and compare them to pure spaced repetition systems like Anki because incremental reading systems do a much better job at allowing the user to enjoy the review process.

Between 2020 and 2022 I spent a lot of time using SuperMemo, read all of Piotr Wozniak's articles, talked to hundreds of people in the SuperMemo.Wiki Discord channel and started a YouTube channel and podcast related to these ideas.

I met ex-gamers who went from spending 8 hours per day playing League of Legends to live-streaming themselves reviewing their incremental reading queue for 8 hours per day.

Many people were not in school (myself included) or had never been to school at all! We didn't have exams to study for. But instead of playing video games, we spent all day using this obscure learning software with a UI like a NASA rocket dashboard.

Instead of watching Netflix, we had month-long debates over whether flashcards ought to be formulated using analogies and made guides about how you should prioritise and value learning material. Why?

The only way to explain it is by breaking down the concept of knowledge valuation.

A Nose for the Interesting

Humans are naturally attracted to information that is surprising, novel, consistent and coherent. Sometimes we are attracted to contradictory information - I think it depends on your personality type. But for the most part, we love information that "slots in" or that we can relate in some way to our prior knowledge and our current goals. Understanding is pleasurable.We don't like information that we can't relate in some way to our prior knowledge. When we are forced to try to understand something when we don't know the pre-requisite concepts, we get bored and frustrated and start yawning.

Semantic Distance

Semantic distance is like the "knowledge gap" between what you already know and some new information input. For example, there's a semantic distance between your current knowledge of mathematics and a new mathematical subject you haven't studied before. When the gap is too large, it makes it impossible to understand the new information because you can't relate it meaningfully to what you already know. If you take a graduate-level math lecture before having studied math 101, it will be impossible, you will display physical signs of displeasure, like fidgeting, restlessness, yawning and more - your body is telling you to go do something else!

Anyone who has used spaced repetition systems at school understands the feeling of needing to drill flashcards into your brain that just won't stick and it's a horrible feeling.

There are two main features in incremental reading systems which avoid this making them much more enjoyable to use - prioritisation and variable reward.

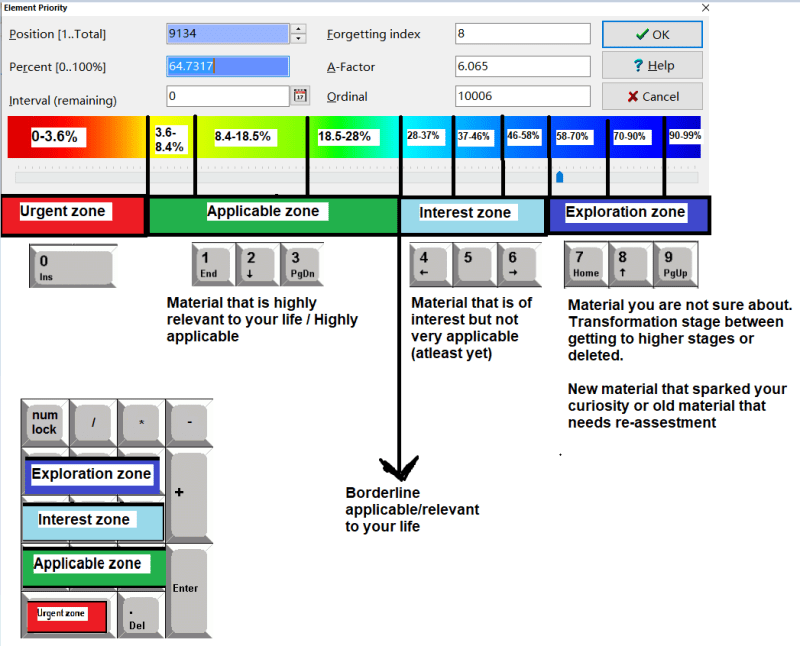

The Priority Queue

Incremental reading systems add prioritisation to the queue, so unlike a pure spaced repetition system, you aren't shown information based only on how likely you are to forget it. You can use the priority system to attach a subjective sense of importance or "interestingness" to each item in the queue. The priority is just a number from 0-100, what exactly it means is up to the user to determine and will likely vary over time as their values and goals evolve.

You are also encouraged to break up large pieces of content into smaller chunks and apply more granular prioritisation mechanisms. This is very similar to the way people chop up clips from long podcasts and upload the highlights to YouTube shorts or TikTok.

This is an improvement over pure spaced repetition because flashcards no longer compete for your attention based on how difficult they are, but also based on how interesting you find them. Since understanding is pleasurable people naturally assign the highest priorities to material that is novel but comprehensible. Any material that is too complex gets sent to the back of the queue. By the time you reach it, you may have built up the pre-requisite concepts for it to become interesting to you.

This works well as long as you are diligent about updating priorities for each flashcard or article in your collection to maintain the mapping between how interesting your brain finds them and their order in the priority queue. But what inevitably happens is that you take a break from the system, your interests change and the priorities you assigned 6 months ago are now out of sync with your current interests. Users end up complaining about "stale collections" of material they used to find interesting, but which they no longer care about.

It would be better if the system could quickly and dynamically adjust what it recommends to you by inferring your interests from your current behaviour, similar to modern recommender algorithms.

Variable Reward

Just having a mixture of different information types in your queue makes it much more enjoyable. It can be draining to read or answer flashcards for hours on end, why not break it up with some more passive sources like YouTube videos?

Incremental reading systems differ from recommender systems in that you are responsible for adding all the material manually into your queue. But as the intervals between repetitions and the amount of items in your collection grows, you tend to forget what you put in your queue, so you can't predict what's coming next. All you know is that whatever comes next is something that you believed was important enough to import and assign a priority. This makes going through your queue surprising. Articles and videos interleaved together with flashcards force seemingly unrelated concepts into your attention in quick succession, often resulting in unexpected connections.

But current incremental reading systems aren't set up to give you completely unexpected content - they rely on you manually going out to search for things. Nor is there any notion of collaborative filtering - incremental reading systems are single-player games. And due to information overload and the degradation in the quality of the search results from Google search, this is becoming more and more frustrating.

YouTube Shorts

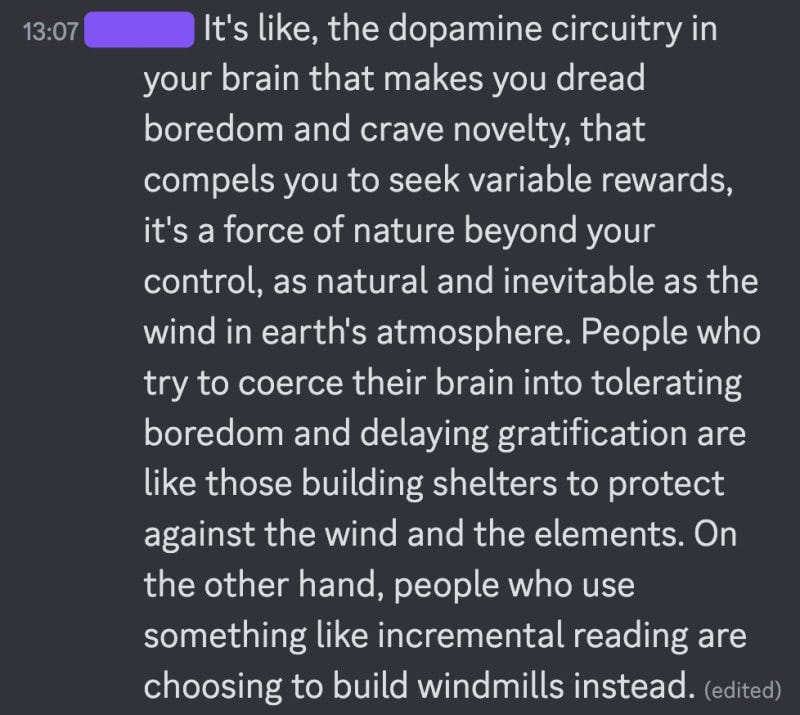

Now let's examine YouTube shorts. Why is it that people are able to kick back and relax at the end of a long day by watching four hours of YouTube shorts, but would despise spending four hours doing flashcard repetitions in Anki?

Why do people willingly forego meals and sleep to watch TikTok but only do Anki repetitions reluctantly?

For spaced repetition apps (and ed-tech apps in general) to take over the world they need to see themselves as competing with Netflix, TikTok and YouTube shorts for users' attention. When you scroll through TikTok or YouTube shorts, you never have the experience of failing to understand something. Everything is perfectly comprehensible. There is the novelty and surprisal aspect of not knowing what is coming next. YouTube shorts is a market of clips competing to entertain you the most. Clips are collaboratively filtered by the community and recommended to you based on your watch history. They have high retention because they allow you to quickly "channel zap" and find something new when you get bored.

But while the user interface and algorithms implemented into YouTube shorts and TikTok make them very engaging, the content quality is often extremely bad. It's hard to curate a feed of really high quality educational content that will advance you towards your goals. These systems are black boxes with little opportunity for customisation. They also lack the active recall aspect of spaced repetition systems which help you internalise and reflect on important concepts.

A Better Recommender System?

Is there potential for a recommender system that blends the best characteristics from spaced repetition, incremental reading and YouTube shorts into one? People will argue that without sensationalist, clickbait content, YouTube shorts and TikTok would lose their addictive power, but my experience in the SuperMemo.Wiki Discord has shown me that people can become hooked on content that improves their life under the right circumstances.

What I dreamt of back in university was a system that could infer my interests from my daily activities, like flashcard reviews, reading behaviour and browsing habits, and use that information to recommend me videos, articles and podcasts from YouTube that I could watch in the evening after school. I never got anything off the ground until a month ago when I revisited Erik Bjäreholt's blog post on Open Recommender Systems and realised that LLMs have made sophisticated, customisable and explainable recommendation systems easier than ever to build!

We need to start exploring what is possible now we can use LLMs as agents, constantly scanning the web on our behalf, searching for golden nuggets that we'll find interesting.

Open Recommender

For the past month I've been working on a proof of concept for an open source recommender system called Open Recommender. Currently it works by taking your public Twitter data as input, uses LLMs to process it and infer your interests and searches YouTube to curate lists of short 30-60 second clips tailored to your current interests. I wrote an article about it and made a video showing an early prototype.

I already have plans to make it even more targeted at an individual's unique interests and prior knowledge - for example it could take arbitrary information sources as input, like the history and probability of recall for all of the information you had added into your spaced repetition system.

I'll also be adding ways to tune the behaviour of the recommender to your personal tastes - the recommendations could exist along a spectrum from appealing to the interests the system knows the learner already has to giving recommendations from new unexplored territory. And because it's implemented using LLMs, you can provide custom instructions using natural language and the LLM can provide understandable explanations for its recommendations.

And I'm also working on an early version of the UI:

If this sounds exciting to you and you are interested in supporting the project, you can subscribe here and I'll include you in the test of the UI before it becomes available to anyone else, as well as implement your feedback ASAP. If you have any good ideas, please get in touch with me on Twitter @experilearning. Thanks for reading!!