Metrics, Optimisation and the Paradox of Deception

Is it possible to track progress towards meaningful goals?

Learning and problem-solving are enjoyable, but progress can be slow with unpredictable payoffs. They both require creativity making the rewards irregular rather than being delivered on a schedule. You can never know when the next mini epiphany will come or when the next piece of the jigsaw puzzle will slot into place.

Metrics seem like an antidote to this uncertainty. They give us a target to aim for, allow us to infer trends and accelerate the feedback loop between action and reward. But at what cost? Over the past 6 years, I’ve repeatedly fallen prey to the siren call of blindly optimising metrics in pursuit of a goal. Everyone knows that metrics can be abused - popular aphorisms like Goodhart's Law and cautionary tales of breeding cobras to sell to the British authorities in colonial Delhi have made it common knowledge. But since there’s no way to compare your current situation with the counterfactual universe where you didn’t use metrics as your compass, not all of the downsides are obvious.

Strongly influenced by Kenneth Stanley’s book, the Myth of the Objective, I’ve been thinking recently about metrics and optimisation in the context of my daily routine. I admit that I am somewhat of a “freak moron” (to quote Zander) when it comes to planning my day to the minute, and I suspect that I may have driven myself into a local optimum. How do I escape?

Tunnel Vision

Here’s me reading the first paragraph from a draft of an article I’m writing about my experience planning my day during a podcast.

The trap I repeatedly fell into during those periods was an excessive focus on one goal at the expense of everything else. In secondary school, it was going to the gym, at the expense of grades and social life. In university, I spent 99% of the time in my room studying instead of making friends. Then after university, it was coding, while other areas of my life fell into disarray.

So there’s an obvious downside to investing all of your time and energy into one area which is that life is multi-faceted and the areas you ignore will either stagnate or regress. But there’s also a hidden cost. The act of setting a specific goal or target kills unexpected opportunities.

Take this bee for example. If the bee sets one particular flower as its target, it will ignore other areas of the environment, even if they contain interesting things worth exploring. The bee optimises for one at the expense of many.

If the bee doesn’t have a goal or uses a less specific goal, its path becomes much more open-ended. Instead of saying “I must visit that flower in particular” it could use a more abstract, generic goal like “I will explore beautiful flowers”. It’s hard to say in advance where the bee will end up, only that it will eventually find something interesting.

The difficulty is that the more open-ended and vague your goal is, the harder it is to explain or justify in concrete terms. For example, I have benefitted in many ways from using Twitter. But Twitter is exactly the kind of thing that gets cut from a routine which over-optimises for productivity, because to defend it you have to use terms like “serendipity” and “stepping-stone collection” which sound like unquantifiable bullshit, even though they are real.

Deception

The underlying assumption behind metrics is that we can rely on them to tell us when we are getting closer or further away from our goals. But like a faulty compass metrics can often lead us astray.

Here’s another bee analogy. If the bee’s goal is to get to the golden nugget, the most obvious metric it could track is the distance away from the nugget. The bee expects that it can use the metric to guide it closer and closer towards its goal. However, it fails to account for the structure of the environment. As long as it sticks stubbornly to its metric it can never escape the dead end local optimum its metric has driven it into.

If the bee wants to escape and achieve its goal, things must get worse before they get better.

I experienced this during my third year of university. I decided I hated the course I was studying and took a year out to live at home with my parents. This was tough because while I didn’t enjoy university, at least it made me seem as if I had a purpose. Taking a year out without a plan was tough socially because it was difficult to explain to curious friends and family what I was doing.

But the abundance of free time I had with little pressure to justify what I was doing gave me the freedom and time required to find what I was really passionate about. In other words it allowed me to cross through the adaptive valley and find a higher peak in the adaptive landscape.

Surrogation

Surrogation describes the replacement of a meaningful end goal with a metric.

An everyday example of surrogation is a manager tasked with increasing customer satisfaction who begins to believe that the customer satisfaction survey score actually *is* customer satisfaction. - Wikipedia page on Surrogation

When the metric becomes the goal rather than a mere indicator, you adjust your behaviour to optimise purely for that metric. And when you optimise purely for metrics, the process becomes disconnected from reality.

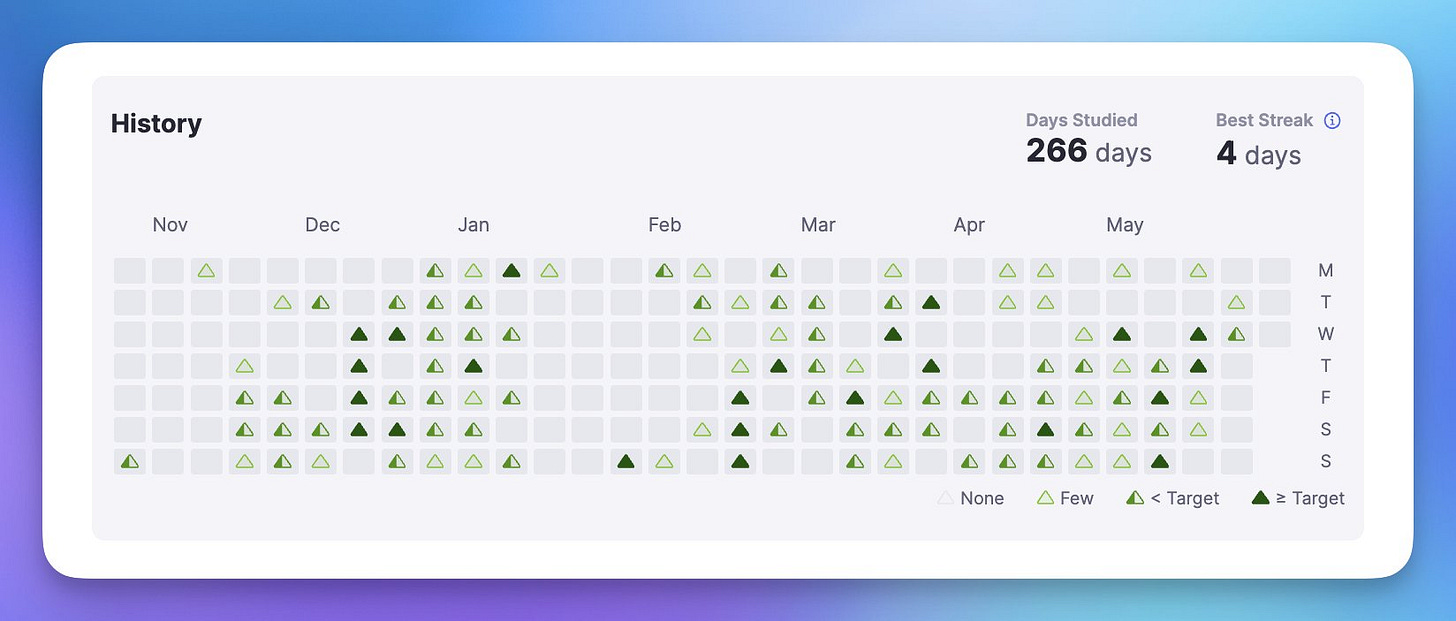

I noticed this frequently in my spaced repetition usage. I love spaced repetition systems (SRS) and I think they have the potential to change the world, but there are plenty of metric-based traps you can fall into. Take the classic flashcard streak heatmap for example. When you don’t focus on it too much, then it’s a useful measure of consistency which is important in SRS because flashcards are scheduled to be reviewed at particular times and missing those times impacts your learning efficiency.

But if you let your heatmap and streak get into your head, you stop seeing meaningful goals as the purpose of your reviews, and instead your reviews become a grind to beat your high score at the flashcard slot machine without it ever culminating in a payoff in the real world.

I’ve certainly fallen into the trap of persisting with reviews of certain branches of my flashcard collection out of a mixture of the sunk cost fallacy as well as a sense of dread at breaking a long streak. But what’s the point of maintaining a streak for the sake of it? Should I feel good about myself if I dutifully persist through a boring 30 minutes reviewing cards I hate? There are a million other things I could be doing, why don’t I choose to do them instead?

So what’s the solution?

I don’t really know. If you have any good ideas, DM me on Twitter so we can discuss them. I simultaneously feel a strong urge to start religiously planning my day again, but I also don’t want to make the same mistakes I made before. Is it possible to strike a balance between metric following and open-ended exploration?

Some scattered thoughts on all this:

- You can schedule open time in the day. Maybe this gets you the best of both worlds of serendipity and optimization?

- Regarding metrics that get trapped in local optima, if there is no path available that optimizes the metric then you should take a path that does Not optimize it. This is what the A-Star algorithm does.

- Try supplementing heat maps and trackers with quick daily reflections. Whatever the tracker's big idea or ultimate goal, jot down a few sentences on how you feel about your engagement with the goal/idea that day. This mixes quantitative and qualitative tracking. Periodically review this reflections.

- Optimizing a single dimension does indeed lead to bad results on all other dimensions. So optimize on several dimensions! Career, Social, and Health is a good basket to start with.