How might we heal the sick man of Europe?

Remember that you are an Englishman, and have subsequently drawn the greatest prize in the lottery of life

“The UK is a miserable country and a bad country for young people to live… There is this culture of misery and pessimism that is quite contagious and it has a really negative effect on the collective psyche… There’s this apathy that comes with it at the same time that actually stops any progress”1

It’s not easy to be a Brit online these days. The discourse is flooded with laments about our economic stagnation and declining prospects.

Yet, there is a paradox at the heart of Britain’s economic woes. We have plenty of talented young people, a stable government, a strong legal system, and well-established institutions. And if domestic funding falls short, foreign VCs are eager to invest in ambitious British ventures.

But despite this we don’t produce nearly as many startups as our American cousins, and our economic growth has been non-existent for more than a decade.

How seriously should we take the idea that our “collective psyche” is what’s holding us back and how might we build a compelling aesthetic of British optimism for the 21st Century?

Pessimistic Pommies

A common refrain is that America thrives on a deeply ingrained cultural optimism - the American Dream, while we Britons are naturally more cynical, looking down our noses and scoffing at such naïveté. But optimism and pessimism aren’t fixed national traits, but moods that rise and fall in response to historical events and the prevailing ideas of the time.

Take Georgian Britain for example. Historian Penelope Corfield spent years collecting eighteenth-century reflections on “the age,” “the times,” or “the century.” Even in an age we now associate with boundless optimism, driven by industrial progress and scientific discovery, prophecies of doom were ever-present. Consider this dramatic warning from a Nottingham minister in 1778:

“Our country bleeds at its heart; our vices have risen to their crisis…and Britain, the envied among nations, the seat of glorious liberty, and science, and law, the refuge of the oppressed, the friend of mankind, is sinking into ruin.”2

Despite such dire proclamations, Corfield observed that that optimism gained cultural dominance during this era. In 1776, the philosopher Jeremy Bentham described his time as “an age in which knowledge is rapidly approaching towards perfection”. A popular song from 1830 captured a similar spirit of excitement about technological progress:

Open your eyes, and gaze with surprise

On the wonders, the wonders to come!3

Britain’s mood, then as now, was never wholly optimistic or pessimistic - it was a contest of competing narratives. If pessimism dominates today, it’s for two main reasons:

First, misleading claims like that global poverty is rising or that the world is getting worse have proven surprisingly persuasive and have led people to distrust the scientific, technological and economic transformations that have raised living standards across the world.

Second, Britain faces genuine challenges like unaffordable housing, the cost of living crisis, high energy prices and a rising crime rate, and young people see no clear path to solving them, creating a sense of despair.4

Manifesting Growth

Optimism and pessimism are not passive reactions to economic cycles or historical circumstances. They are actively shaped, often by great founders - whether religious leaders, philosophers, statesmen like Churchill, or the visionary US entrepreneurs from the 1980s.

If we were to craft an aesthetic - a national vision - to tell a compelling story of British growth in the 21st century, one that aligns with the opportunities of our time, what would it look like?

The Anglofuturist movement and podcast have already done great work here, broadcasting conversations with ambitious guests working on geothermal energy, artificial wombs and new islands in the North Sea - all from their orbital thatched pub, the King Charles III Space Station.

To return to the paradox we began with: Britain has all the ingredients for success. Talented young people, a stable government, a strong legal system, and well-established institutions. Is the missing piece simply the ability to galvanise them under a shared vision?

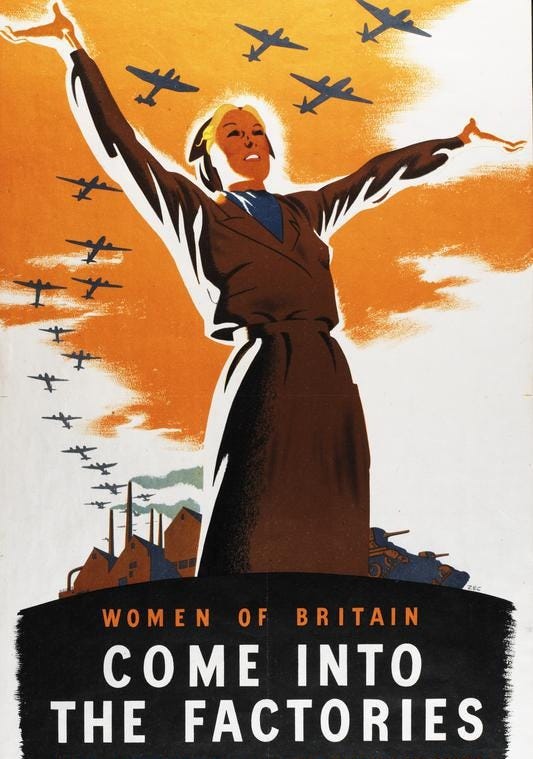

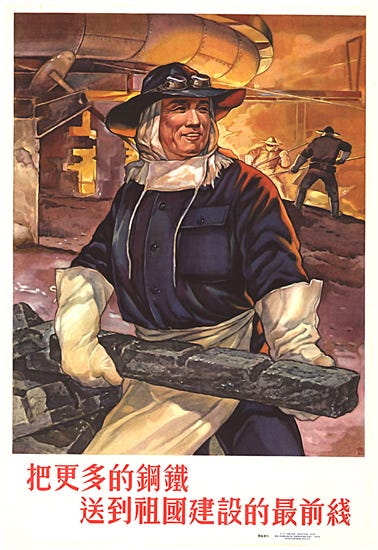

Looking to history, what can we learn from past efforts to mobilise societies toward ambitious goals? How did pre-industrial Russia and China move millions of peasant farmers into industrial production? How did wartime governments inspire women to take up factory work to support the war effort?

Take a look at these propaganda posters:

They created an attractive aesthetic of industrial scale, builder-led optimism…

They placed people at the focal point, as the agents of change…

They wove individual effort into a meaningful cause…

These campaigns crafted a clear, compelling narrative for the population, showing them their role in building the future.

And this approach maps surprisingly well to our current moment:

With AI and automation, everyone’s capabilities have increased a thousandfold. What’s scarce is not rare talent - but the will and courage to use these new tools to work on the world’s hardest problems.

Let’s build

As a first step towards that, here’s my humble pitch as a Brit sick of the pessimism and misery online:

I’m an ex-SWE from Oxford. I quit my job 5 months ago to find something more interesting to work on. Here’s what I’ve tried so far:

Other misc experiments: code agents, drum synth, writing, podcasts

Now: DSPy-inspired library for text-based gradient descent (WIP)

I’d love to meet people interested in meeting up London to work together on a two-week project to build something interesting. Such as:

Interested? Please message me on Twitter @experilearning or Discord.

Thanks for reading!

The Evolution of Culture by David Deutsch

Optimism and Pessimism - Our World in Data

“only 41 per cent of those aged 18 to 27 are proud to be British… In 2004, some 80 per cent of young people in the same age cohort said that they felt proud to be British” - Pride in Britain? It’s history

We love to see this kind of optimism. Thanks for the kind words!